by Kiernan Mathews, Todd Benson, Sara Polsky, and Lauren Scungio

Since 2005, the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education’s (COACHE) Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey has been systematically listening to faculty and, campus by campus, revealing inequities in the faculty experience. The survey results illuminate disparities in perceptions about the academic workplace between faculty of different racial and ethnic backgrounds—and also demonstrate, amid a nationwide conversation about inclusion, that white faculty’s perception of diversity and inclusion efforts on campus still outpaces genuine progress.

Since 2005, the Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education’s (COACHE) Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey has been systematically listening to faculty and, campus by campus, revealing inequities in the faculty experience. The survey results illuminate disparities in perceptions about the academic workplace between faculty of different racial and ethnic backgrounds—and also demonstrate, amid a nationwide conversation about inclusion, that white faculty’s perception of diversity and inclusion efforts on campus still outpaces genuine progress.

This phenomenon, which Julian Vasquez Heilig, Keffrelyn Brown, and Anthony Brown dubbed “the illusion of inclusion,” shows up across several dimensions of the analytics COACHE delivers to college and university leaders.

Gaps in Perceptions About Support for Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

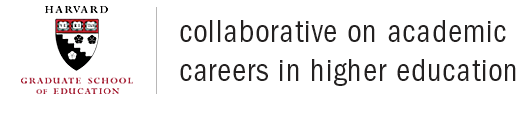

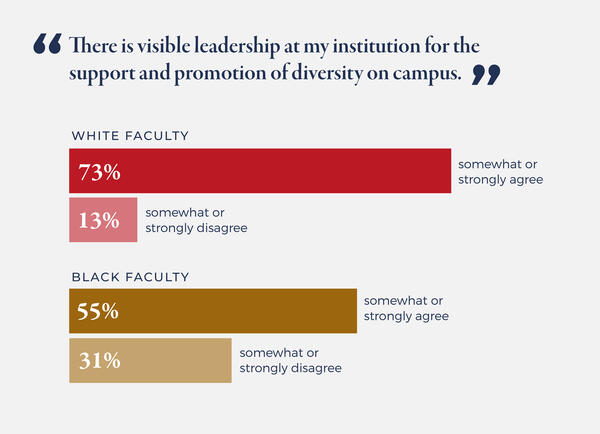

This illusion appears in COACHE survey measures about whether faculty perceive visible leadership from campus leadership for the support and promotion of diversity on campus, a commitment to supporting and promoting diversity and inclusion among departmental colleagues, and a sense of belonging in their departments.

White faculty are much more likely to agree (73 percent) than are Black faculty (55 percent) that there is visible leadership for the support and promotion of diversity on their campus. Nearly one out of every three Black faculty (31 percent) disagrees:

† Source: Mathews, K. R., Benson, R. T., Trower, C. A., Azubuike, N. O., & Kumar, A. (2017). The Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education: Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey, 2012-2017 (Research version) [data file and codebook]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

By an even wider margin, more white faculty (78 percent) than Black faculty (58 precent) agree that their department colleagues are committed to supporting and promoting diversity and inclusion in the department. More than one out of every four Black faculty (28 percent) disagrees:

† Source: Mathews, K. R., Benson, R. T., Trower, C. A., Azubuike, N. O., & Kumar, A. (2017). The Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education: Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey, 2012-2017 (Research version) [data file and codebook]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University.

Although departmental “fit” is problematic in hiring and promotion, research suggests that a faculty member’s feelings of fit produce workplace benefits such as greater job satisfaction and likelihood of retention. The advantages of fit, we find, are enjoyed more often by white faculty, who to a greater extent than any other racial or ethnic category report feeling satisfied or very satisfied (69 percent) with their fit—their sense of belonging—in their departments.‡

Table 1. Rate your satisfaction or dissatisfaction with how well you fit in your department (e.g. your sense of belonging in your department).

| White, non-Hispanic | Asian, Asian-American or Pacific Islander | Hispanic or Latino | Black or African American | All Others | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfied or Very satisfied | 69% | 67% | 62% | 62% | 62% |

| Dissatisfied or Very dissatisfied | 18% | 15% | 23% | 21% | 23% |

‡ Source: COACHE Summary Tables 2019: Selected Dimensions of the Faculty Workplace Experience, by Institution Type, Discipline, Rank (with Tenure Status), Race/Ethnicity, and Gender.

These impressions—white colleagues’ stronger sense of campus leadership on diversity; their more optimistic belief in their colleagues’ commitment to inclusion; and their greater sense of belonging in their departments—conjure for Black and African American faculty and other minoritized groups an unfulfilled promise of an inclusive academy.

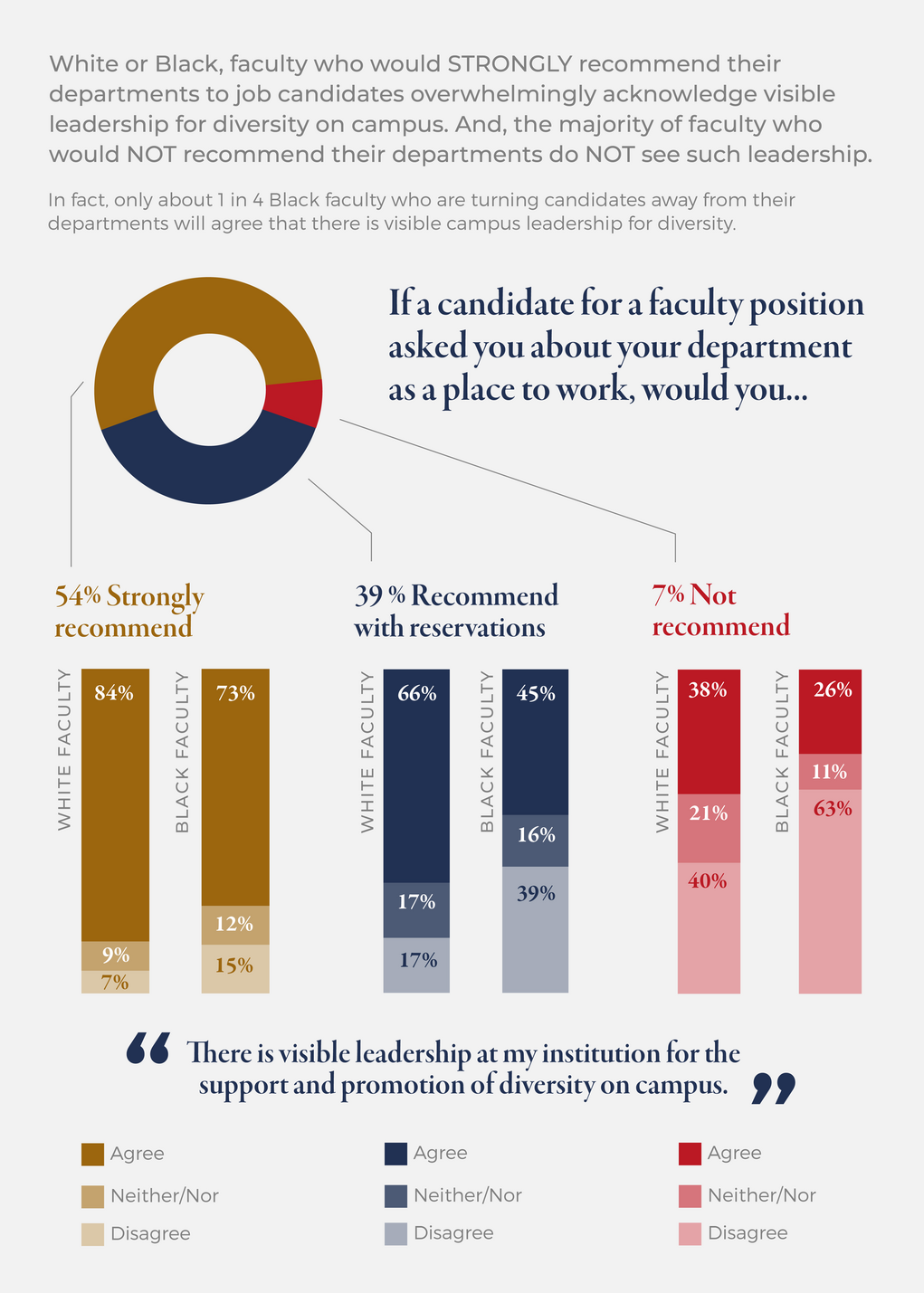

The perception gaps between white and Black department colleagues threaten not just retention, but hiring, as well. White or Black, faculty who say they would strongly recommend their departments to job candidates overwhelmingly acknowledge visible leadership for diversity on campus. The majority of faculty who would not recommend their departments do not see such leadership.

Among Black faculty who strongly recommend their departments, nearly 3 in 4 (73 percent) agree that there is visible leadership for diversity, but only about 1 in 4 (26 percent) Black faculty who would turn candidates away agree that there is visible campus leadership for diversity.

† Source: Mathews, K. R., Benson, R. T., Trower, C. A., Azubuike, N. O., & Kumar, A. (2017). The Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education: Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey, 2012-2017 (Research version) [data file and codebook]. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University

From Dispelling the Illusion to Building a New Academy

According to evidence-based guidance from our partners at the Aspire Alliance Institutional Change Initiative, “Potential candidates are attentive to the signals that they receive about the campus climate, observing the extent to which women and men of color are welcomed and included in their departmental and campus-wide communities, as well as whether diversity is treated as an institutional priority.”

College leaders must do better to connect their performative support of diversity and inclusion with the everyday behaviors of faculty, and especially white faculty, in their departments. Presidents, provosts and deans know by now that traditional evaluation criteria value the kind of work done by white faculty (especially white men), particularly scholarly productivity, over the work that faculty of color are more often asked to perform, including teaching, mentorship, and other departmental service work. So, if these leaders are intent on institutional transformation, they will work with faculty to reward in tenure and promotion all of the contributions that faculty from diverse backgrounds make to the university.

To begin, college leaders and white faculty can dispel the illusion of support and promotion for diversity. By working on themselves, they can start to make inclusion a reality and institutions of higher education more attractive and equitable places to work.