by Sara Polsky

by Sara Polsky

The COVID-19 pandemic has made questions of trust between faculty and institutional leadership more urgent than ever, as the events of the last year have increased the distance, literally and figuratively, between faculty members and administrators.

COACHE’s Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey partners often use the survey—from pre-launch to sharing the survey results—to raise and address issues of trust on campus.

Asking Faculty About Trust

Academic administrators tend to think about trust on a practical level, as many of them told COACHE for a report we produced on five ingredients of effective academic governance. They see trust as a key element of shared governance and a result of clear expectations and transparency around the governance process.

Researchers Wayne K. Hoy and Megan Tschannen-Moran define trust as “an individual’s or group’s willingness to be vulnerable to another party based on the confidence that the latter party is benevolent, reliable, competent, honest, and open.” Researchers have also highlighted openness, competence, and reliability as characteristics of trusting relationships between faculty members and administrators. Where trust is absent from the workplace, employees are likely to be less engaged in their work and to experience more workplace stress. They may be less likely to stick with their jobs over the long-term.

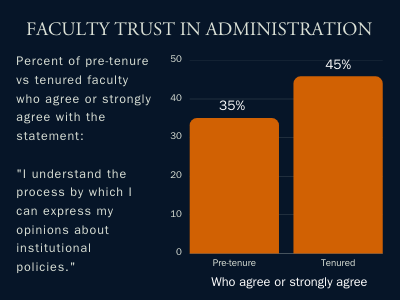

From COACHE’s research on the ingredients of effective academic governance, we crafted five shared governance modules of the Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey. One section asks a series of questions about trust, seeking to evaluate faculty’s understanding of the institutional process for sharing their opinions, the clarity of faculty and administrator roles on campus, and the system for faculty-administration communication.

The aggregate COACHE survey results indicate that tenured faculty members feel a stronger sense of trust toward administrators at their institutions than pre-tenure faculty. In response to a survey question about faculty’s understanding of the process for expressing their opinions about institutional policies, 45.8 percent of tenured faculty said they agreed or strongly agreed that they understand that process, compared to 35 percent of pre-tenured faculty.

“To get at trust,” one provost said in interviews for the 2015 whitepaper, “you have to ask: what are people’s expectations going in?” Some institutions codify those expectations more concretely than others in union contracts or bylaws; institutions where expectations are more implicit may find themselves struggling with a lack of role clarity or confusion around who has the authority to make decisions. Because faculty members often stay at their institutions for many years, or even for their entire careers, breaches of trust can linger long past the incidents that caused them.

“To get at trust,” one provost said in interviews for the 2015 whitepaper, “you have to ask: what are people’s expectations going in?” Some institutions codify those expectations more concretely than others in union contracts or bylaws; institutions where expectations are more implicit may find themselves struggling with a lack of role clarity or confusion around who has the authority to make decisions. Because faculty members often stay at their institutions for many years, or even for their entire careers, breaches of trust can linger long past the incidents that caused them.

Using a Survey to Improve Trust on Campus

The choice to use an external, benchmarked survey rather than an internal one can be a step toward rebuilding campus trust, as faculty who might otherwise be worried to speak out are assured of the confidentiality of the data. When institutions partner with outside groups, those third parties can mitigate concerns about design and research methodology.

Institutions can also make decisions throughout the survey process that prioritize building or regenerating trust between administrators and faculty. At the University of Denver, administrators used the survey as the first test case for a data governance committee that included faculty members.

Administrators at Georgia State University chose not to receive the raw data from the Faculty Job Satisfaction Survey. “There has been some distrust between the faculty at Georgia State and the administration,” said Michael Galchinsky, Associate Provost for Institutional Effectiveness at GSU. “Because we knew that going in, we decided to take that step of not receiving the raw data in order to increase the trust.” The university disseminated the data it did receive to faculty through the institution’s learning management system and subsequently used the data as the foundation for a series of campus dialogues, all in service of regenerating trust.

Such efforts are particularly important in moments of challenge or crisis, as several provosts told COACHE researchers in conversations about shared governance. As administrators pointed out in our 2015 research, trust can push institutions forward and, in difficult moments, make them more resilient, as faculty and administrators who trust each other “empower each other to make decisions.” Building that trust is a process that begins with listening to faculty.

To learn more about COACHE engagement as a path to trust-building between faculty and administration, schedule a call with our team.